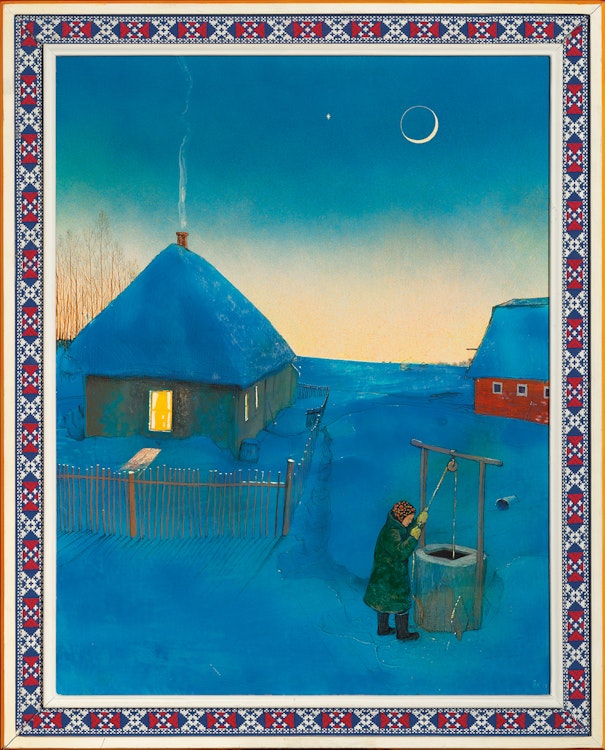

Pioneer Homestead on a Winter’s Evening by William Kurelek

William Kurelek

Pioneer Homestead on a Winter’s Evening

mixed media on board

signed with monogram and dated 1971 lower right; titled on the reverse of the artist’s frame

24.5 x 19 ins ( 62.2 x 48.3 cms )

Auction Estimate: $50,000.00 - $70,000.00

Price Realized $82,600.00

Sale date: November 19th 2019

Acquired directly from the artist

Private Collection, Ontario

William Kurelek, The Ukrainian Pioneer Woman in Canada: A Series of Twenty Paintings by William Kurelek, The Isaacs Gallery, Toronto, 1968, not paginated

The seeds of the artist’s approach to the Canadian terrain were actually sown as early as 1964. That year he dedicated An Immigrant Farms in Canada, a series exhibited at Toronto’s Isaacs Gallery, to the migration experience of his parents’ family, especially his Ukrainian father. Kurelek followed An Immigrant Farms in Canada with The Ukrainian Pioneer Woman in Canada, a tribute to the artist’s mother, which was exhibited at the Ukrainian Pavilion at Expo ’67 in Montreal. The production of this series had been encouraged by the Toronto branch of the Ukrainian Women’s Association of Canada. Members of the association – including the collector who eventually acquired “Pioneer Homestead on a Winter’s Evening” – also had ties to the Ukrainian Women’s Institute of St. Vladimir, on Spadina Avenue.

The painting pictures a woman drawing water from a well at night on the Canadian Prairie in winter. The main thatched- roof structure is what Kurelek, in an explanatory text he composed for The Ukrainian Pioneer Woman in Canada, referred to as “the second house”: after the “burdei,” the “first real home of the Ukrainian settler...modeled after the homes they knew in the old country and usually ‘home-made’ thriftily with the materials at hand.” “Pioneer Homestead on a Winter’s Night” also evinces Kurelek’s skill as a professional picture framer. The painting’s surround combines two elements that recur throughout many works the artist produced about the lives of his immigrant ancestors: barnboard retrieved from his father’s farm outside Hamilton, and vyshyvka, traditional Ukrainian folk embroidery.

“Pioneer Homestead on a Winter’s Night” was produced at a time when Kurelek, a devote Roman Catholic, often peppered his work with mixed messages. Many of his paintings from this period oscillate between, for instance, heroically celebrating the economic progress of the Ukrainian diaspora in Canada, on the one hand, and castigating the hubristic excesses of a society that, having turned from God, teetered on the edge of apocalyptic calamity in the nuclear age, on the other. While “Pioneer Homestead on a Winter’s Night” is clearly concerned with the former, it hints at a darker theme. Although the painting’s nostalgic mood, along with the bright dog star, waxing sickle moon, and the home’s luminous interior, convey comfort and optimism, the night’s cold, enveloping blackness undercuts the scene’s otherwise placid simplicity. Kurelek felt deep appreciation for natural beauty, but he often sought, through landscape, to remind the viewer that, “Nature gives not a drop of comfort, can do nothing, will do nothing...living beings are trapped by her pitiless laws.”

We extend our thanks to Andrew Kear, Canadian art historian and Head of Collections, Exhibitions and Programs at Museum London for contributing the preceding essay. Andrew is the past Chief Curator and Curator of Canadian art at the Winnipeg Art Gallery, a Curator of the 2011/2012 national travelling exhibition William Kurelek: The Messenger and author of the Art Canada’s Institute’s William Kurelek: Life & Work, available at www.aci-iac.ca.

Share this item with your friends

William Kurelek

(1927 - 1977) RCA

Born on a farm near Willingdon, Alberta in 1927, William Kurelek created paintings that explored the reality of farm life during the Depression, with a focus on Ukrainian experiences in Canada. Kurelek’s mother’s family settled in Canada during one of the first waves of Ukrainian immigration in 1899 before the painter’s father arrived in Alberta from Western Ukraine during the second major wave to the province in 1923. In 1934, Kurelek’s family moved to Manitoba, near Winnipeg, due to falling grain prices and a fire that destroyed their home. Upon moving to Manitoba, Kurelek began attending school at the Victoria Public School.

Influenced by the apprehension surrounding the Depression, World War I, and the instability of farming, Kurelek focused on his studies. However, his father did not approve. While Kurelek’s father valued physical labor on the farm, Kurelek concentrated on school and drawing, which caused tension in his household. As a child, Kurelek covered his room in drawings from literature, dreams, and hallucinations. At school, Kurelek’s classmates were enthralled by his stories and drawings.

In 1943, Kurelek and his brother attended Isaac Newton High School in Winnipeg. While in Winnipeg, he frequented Ukrainian cultural classes offered by St. Mary the Protectress. In 1946, Kurelek enrolled in the University of Manitoba studying Latin, English, and history. While in university, Kurelek’s mental health spiraled, which he later self-identified as depersonalization.

After university, in 1948, Kurelek’s family relocated to a farm near Hamilton, Ontario. The next fall, in 1949, Kurelek began studying at the Ontario College of Art working towards a career in commercial advertising. While in school he was uninterested in the competitiveness and emphasis on earning high grades. So, he decided to study with David Alfaro Siqueiros in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico. During his hitchhike to Mexico, Kurelek experienced his first mystical experience while sleeping in the Arizona desert. In this vision, a robed figure asked him to look after his sheep. Upon his arrival to Mexico, Kurelek learned that Siqueiros had departed, and the program was under new direction by Sterling Dickinson. Dickinson’s program was more informal and allowed Kurelek to become aware of social issues and develop his belief system.

Kurelek returned to Canada in 1951 and traveled to England in 1952 where he was admitted into a psychiatric treatment center at London’s Maudsley Hospital. The doctors noted the severity of his illness as well as his artistic talent. After his discharge, Kurelek traveled throughout Europe to view works by Northern Renaissance painters, such as Jan van Eyck and Hieronymus Bosh. In 1953, Kurelek was readmitted into Maudsley, then transferred to Netherne Hospital in Surrey, which had a cutting-edge therapy program. He continued to paint during this time. In early 1955, Kurelek was discharged and returned to London where he worked at an art framing studio, apprenticing with Frederick Pollock.

“Stephen Franklin in ’Weekend Magazine’ described his years in England as follows, ‘In seven years Kurelek found both happiness and sadness in London. His painstaking fool-the-eye paintings of pound notes and other objects found their way into three Royal Academy summer shows, but he was increasingly bothered by eye trouble for which there was no physical cause. He plumbed the depth of emotional despair, contemplated suicide, and wound up in hospital for more than a year. It was here that he began his conversion – from boyhood membership in the Orthodox Church and subsequent atheism – to Catholicism which has deeply affected his life since.’

It was there that he drew many self-portraits and scenes of farm life from his youth. He also developed his unique style of outlining the drawing with a ballpoint pen, using coloured pencils for texture and adding details in pen. Careful examination of his drawings reveals images full of realism with minute details of things like cots, clothes and even insects. Under the pen of William Kurelek, prairie farm scenes and landscapes came to life.”

Kurelek permanently returned to Canada in 1959. Later that year he met Avrom Isaacs, of Isaacs Gallery, who invited him to work in his gallery’s frame shop and hosted his first solo exhibition in 1960. In 1962, Kurelek married Jean Andrews and they relocated to the Beaches area in Toronto. Following the Cuban Missile Crisis, he began painting in a “fire and brimstone” style and constructed a fallout shelter in his basement, which eventually became his studio. He visited Ukraine in 1970 and 1977 and during this period he took a multicultural approach to his art. After his second trip to Ukraine he was admitted to St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto and soon passed away from cancer.

Literature Sources:

Andrew Kear, “William Kurelek: Life and Work”, Art Canada Institute, Toronto, 2017 (https://aci-iac.ca/art-books/william-kurelek)